Racism hiding in public school funding

May 19, 2022

Kandice Sumner is an educator at an inner-city public elementary school in Boston. Born and raised in urban Boston, Kandice graduated from a suburban school system through a voluntary desegregation program,Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity. (METCO). She was one of many lower-income black kids who essentially won the education lottery.

As a young child, she wondered why other kids from her neighborhood didn’t have a similar experience to hers. She says, “At five years old, I thought everyone had a life just like mine. I thought everyone went to school and were the only ones using the brown crayons to color in their family portrait, while everyone else were using the peach-colored ones… As I got older, I started noticing things, like how come my neighborhood friends don’t have to get up at five o’clock in the morning and go to a school that’s an hour away?” In her TED Talk, she explains how she felt that the resources she had access to weren’t meant for her: “I wasn’t supposed to have theater departments with seasonal plays and concerts, digital, visual performing arts. I wasn’t supposed to have fully resourced biology or chemistry labs…freshly prepared school lunches, or even air conditioning… These are things my kids don’t get.”

As an educator primarily in neighborhoods similar to the one she grew up in and very different from the one she went to school in, the differences stare her down every day.

Despite the clear importance of education and an equitable public education system, students living in different counties, cities, or towns within the same state can have drastically different experiences due to their schools’ access to resources and funding, and this translates to how these students proceed with their lives after secondary school. In Sarah Mervosh’s article, How Much Wealthier Are White School Districts Than Nonwhite Ones? $23 Billion, Report Says for The NY Times, she references recent data based on census data, by the nonprofit Edbuild. Judging this data, we know that students from high-income families living in wealthier neighborhoods (primarily white and Asian students) tend to have better funding and more college preparatory programs; therefore, they get into college at a higher rate (consistently 83%) while lower-income (primarily black and Hispanic students) living in less wealthy neighborhoods get into college at a fluctuating 64%. It’s not just about getting into college; as outlined in The Pew Research Center article, Demographic trends and economic well-being, (statistically often lower-income) black and Hispanic students also graduate high-school at a lower rate than white students, and they’re less likely to have a college degree. All of this starts with the quality and the funding of our public schools.

According to Jake Frankfeild in his article Funding Gap, with Investopedia, “a funding gap occurs when there are not enough funds to finance operations.” It’s not uncommon for public schools to hit this point, but what’s interesting is how big the gap is and what the majority demographic is in schools and counties with the most significant gaps. 82% of local public school funding comes from local property taxes, which means that wealthier kids who live in more expensive houses tend to get better-funded schooling.

According to the Education Trust’s analysis “Funding Gaps 2018,” school districts with the greatest concentrations of black, Latino, or Native American students receive around $1,800 less per student than districts educating the least students of color. Between low-income and high-income areas, the funding difference on average is about $1,000 per student.

Northwestern University economist, C. Kirabo Jackson found that when school funding for low-income schools is increased substantially, it results in boosted adult wage, decreased high school dropout rate, and increased graduation rate. He also found that increasing individual student funding by 22% eliminated the achievement gap between low-income and high-income students.

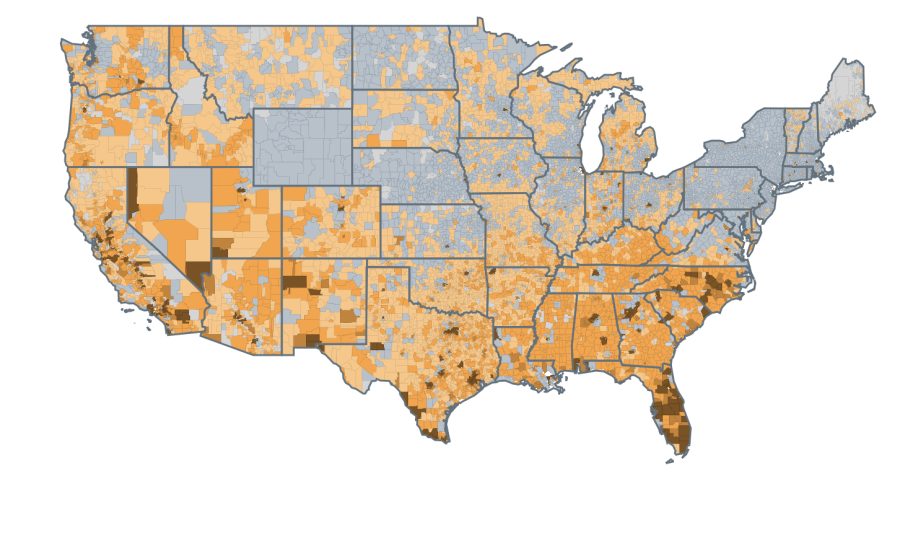

The Century Foundation, a New York-based think tank aimed at reducing inequality, hosts an interactive education funding gap map on their website. According to their data, “Districts with high concentrations of students living in poverty are more likely to have funding gaps, and these students experience significantly larger funding gaps than wealthier districts…Districts with high concentrations of Latinx and Black students have much larger funding gaps and are more likely to have funding gaps, to begin with, than majority-white districts…Nationally, districts with over 50 percent Black and/or Latinx students face a funding gap of more than $5,000 per pupil on average. Black students are disproportionately concentrated in poorly funded, low-performing districts.”

According to the map, in Maryland alone, Baltimore has a vastly disproportionate gap rate in comparison to a state that only has three counties with this disparity. With a difference of $434,093,152 and $5,536 per pupil, Baltimore’s gap is significantly larger than the other MD counties with gaps, (Cecil, Somerset, and Dorchester;) A likely reason being, Baltimore is 61.8% black or African American. In fact it’s the only county in MD with a majority black population.

A fair and equitable public education system is a strict necessity; students deserve a system that is not dependent on their families being a part of a group on a higher rung of the metaphorical socioeconomic ladder. The price of someone’s house or the neighborhood they live in should not determine the quality of their education or their future prospects. Unfortunately, and as of right now, that’s not the way the world works, while steady progress is being made, there are always groups seeking to roll back the strides made and legislation passed. A student’s future rests on the education they receive from a young age; as Kandice Sumner puts it, “The quality of your education is directly proportional to your access to college, your access to jobs, your access to the future.”

Eduardo Polón • May 25, 2022 at 5:14 pm

Thank you for the time, attention, and research put into this quality piece of writing.