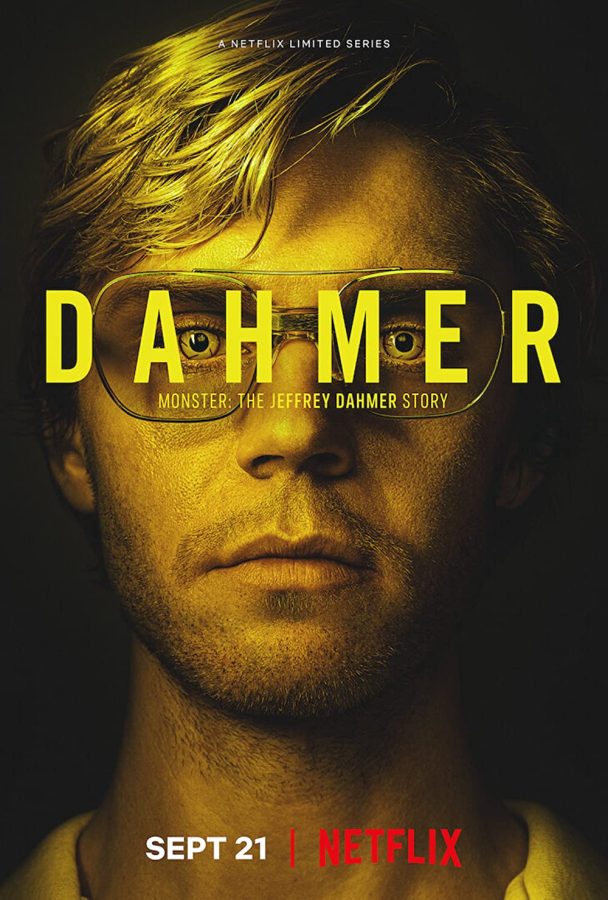

Netflix’s Dahmer and the exploitative nature of true crime

On September 21, 2022, Netflix released the show Dahmer–Monster; The Jeffrey Dahmer Story starring Evan Peters as the infamous American serial killer. Despite the lack of publicity before release, it was quickly a smash hit and became the third most-watched show on Netflix.

One day after its release, a cousin of one of Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims, Errol Lindsey, tweeted that his family is angry about the show and that it was “retraumatizing” their family.

He wasn’t the only upset family member. Errol Lindsey’s sister wrote an essay for Insider Magazine, where she said that “It’s sad that [Netflix] is just making money off of this tragedy. That’s just greed.” The mother of another one of Dahmer’s victims, Tony Hughes, denounced the TV show and said that “it didn’t happen like that.” She then said that she was not consulted about the show, a fact that Lindsey’s cousin echoed. He stated that creators of Dahmer and other media like it claim that they are honoring victims’ families, when in reality, “no one contacts them.” And that making Dahmer and other shows like it are “cruel.”

This claim is in direct contrast to Dahmer’s showrunner, Ryan Murphy. He alleged that he and his team reached out to several members of the victims’ families, none of whom got back to them.

The problem is that true stories and crimes are legally considered public records. Showrunners are under no obligation to compensate or involve families in the dissection of their loved ones’ stories.

Brooke Preston was murdered in 2017 by her roommate. Her killer’s defense was that the murder was done while he was asleep. He was later convicted and sentenced to life in prison. In 2021, Hulu released a documentary, Dead Asleep, about the crime. The documentary includes interviews with Preston’s murderer and focuses on his defense and whether he killed her while sleepwalking. In an interview, the director of Dead Asleep said that she wanted people to ask the question after watching, “Is it possible to kill someone in your sleep?” Immediately after learning about it, Preston’s family panned the documentary and began campaigning against it. Brooke Preston’s sister, Jordan Preston, created a petition, which as of today, has 150,000 signatures calling for the show not to be released. In the petition, she states that she and her family “do not approve of [the show]” and “do not want it ever aired.” She also stated in an interview that the creators did reach out to the family for interviews, but her family refused after learning the documentary would focus on Brooke Preston’s killer.

Even after the documentary was released, Jordan continued to fight for its removal from the streaming platform. In June of 2022, the airline Delta contacted her and told her they would remove the documentary from their services. Jordan said in a Tiktok video, “Never stop fighting for the ones you love.”

Another example of true crime exploitation is a fictionalized tv show, The Thing About Pam, which follows Pam Hupp and her murder of Betsy Faria. The show stars Renée Zellweger as Hupp and has a black comedy aspect. Faria’s daughter, Mariah Day, called the show a “mockery” of what happened, and that there are moments on screen that never actually occurred.

In a series of Tiktoks, she condemns the creators of The Thing About Pam and Zellweger, stating that the actress was “glorifying a murderer.” Mariah Day continues to speak out against the show and the exploitation of her mother’s story on her Tiktok.

The question to ask ourselves now is, why do we feel entitled to victims’ stories? Why do we feel entitled to watch fictionalized versions of real events for our own entertainment?

It would be remiss to ignore the fact that true crime media can have a positive impact.

There is more than one example of a piece of media causing a years-old cold case to be reopened. For example, the podcast, Up and Vanished, details documentary filmmaker and podcast co-creator Liam Payne’s investigations.

Season 1, released in 2016, followed Payne’s examination of Tara Grinstead, a high school teacher who disappeared in 2005. The podcast brought national attention to the case and reinvigorated the search for the truth of what happened.

In 2017, two men were arrested on suspicion of involvement in Grinstead’s death. Neither of the men was charged with murder, only covering up her death.

An example a little closer to home that shows the difference true crime media can make is the podcast Serial.

Adnan Syed was convicted of the 1999 murder of his girlfriend, Han Min Lee, in 2000 in Baltimore County, MD. He was sentenced to life in prison at 17 years old. Throughout the trial, Syed maintained his innocence. In 2014, Serial released twelve episodes about the case. The series details suspicious facts, like how Syed’s DNA was never tested against evidence recovered at the scene. And that his lawyer did not contact someone who gave Syed an alibi. The lawyer was later removed from the bar association after multiple complaints from clients.

Serial became a nationwide phenomenon and was downloaded over 100 million times.

In 2016, Syed was granted a new trial, against Han Min Lee’s family’s wishes. And this year, in 2022, the conviction was overturned due to testing revealing Syed’s DNA was never found at the crime scene.

More than 20 years after he was convicted, Adnan Syed walked free.

So where does that leave us now?

True crime media continues to exist in a murky gray area, having done real good and real harm.

It’s important to continue to ask ourselves, every time we put on a documentary or turn on a podcast, who are the real people behind these stories? Are their stories being told respectfully? Who is benefitting from this being made and shown? Is it the families of the deceased or the victims themselves? Or is it just another example of exploitation?

Hi! My name is Cameron and I'm a senior. This is my third year writing for Wildezine and my second year as an editor. I'm mainly interested in how pop...

Bethany Gagas • Nov 23, 2022 at 5:00 pm

You made puissant counter-points on the helpfulness of true crime media in re-opening cold cases.