One drop of blood test: billions of lies behind a billionaire

“One tiny drop changes everything,” the slogan of Theranos claimed. In 2003, 19-year-old Elizabeth Holmes was inspired by entrepreneurs such as Steve Jobs and dropped out of Stanford University to start her own corporation called Theranos in Silicon Valley with her innovative blueprint: one drop of blood test. At first, it undoubtedly sounded like a revolutionary invention and indeed made a splash in the healthcare industry. While other existing blood testing technologies all required one vial of blood for each diagnostic test, Theranos claimed that they were able to perform hundreds of tests, from a simple cholesterol check to complex genetic analysis, by only collecting one drop of blood from a finger prick.

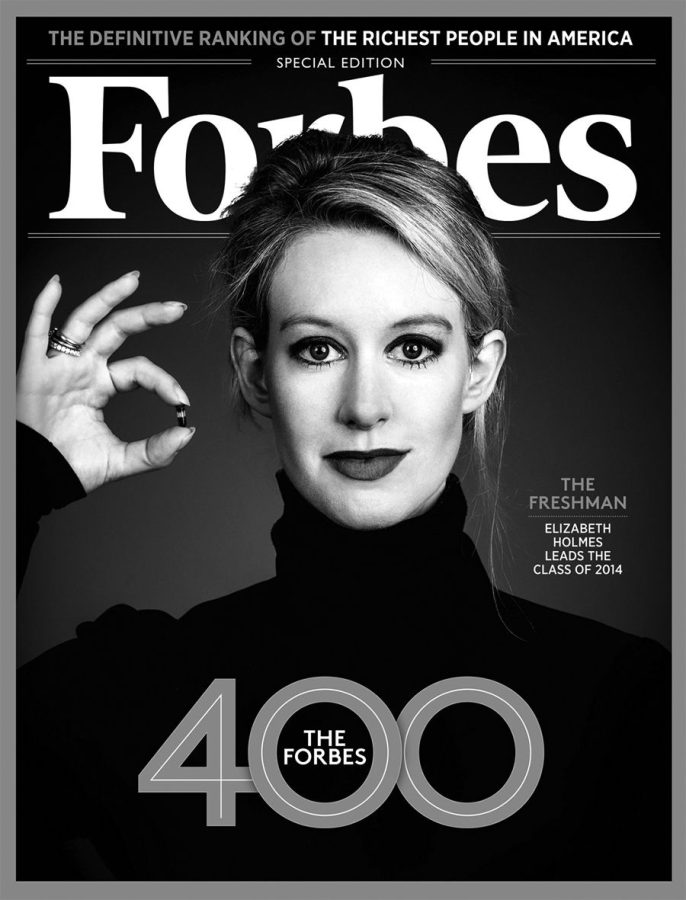

With this ground-breaking idea, Theranos attracted investors such as Tim Draper and The Oracle founder and executive chairman Larry Ellison and gained partnerships with companies such as Safeway and Cleveland Clinic. In fact, according to Crunchbase, from its founding until its shutdown, “Theranos raised around $1.3 billion in funding”. Not only attractive to investors, the blood testing technology from Theranos impressed the public at the beginning as well. At the peak of its success, Theranos sold over 1.5 million blood tests that yielded 7.8 million test results for approximately 176,000 consumers by operating 40 centers inside Walgreens stores in metro Phoenix. Theranos’s advertisement of the one drop of blood testing succeeded due to the mind-blowing characteristics of its technology: faster and more accurate diagnosis results while inexpensive and more convenient than other conventional methods. Along with the rise of Theranos, its founder Elizabeth Holmes herself acquired wealth and fame. In 2015, Holmes reached a net worth of $4.5 billion, achieving the title of America’s Richest Self-Made Woman on Forbes’s annual list.

However, Holmes’s glory did not last long. Theranos’s innovative technology of using only one drop of blood for medical testing soon began to reveal problems. First to appear were the inaccurate results of the Theranos blood test. When a standard blood sample is collected, only half of the sample will typically be useful for the diagnostic test since the blood evenly consists of solids and liquid in half. For example, the complete blood count test (CBC), one of the common diagnostic blood test types, measures the quantity, size, and types of the blood cells which only contain in the solid portion of the blood, while the other common types of the blood test, such as the comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), measure the amount of protein or sugar in the liquid portion of the blood. Hence, conventional blood testing technologies all require one vial of blood for each diagnostic test to ensure adequate measured cells or substances to be collected. Therefore, unlike the uncontaminated blood taken directly from a vein, the small number of drops of capillary blood samples used by Theranos led to inaccurate diagnostic results when it came to the complex health tests. Many Theranos customers were diagnosed with health problems or diseases that they did not have. For example, a healthy person could be diagnosed with HIV and a healthy pregnant woman could be reported to have a miscarriage by Theranos tests. As a result of its false advertisement and inaccurate results, the healthy customers who trusted Theranos’s technology suffered through the emotional distress of the diagnosis that should not be made, while the customers with genuine health problems were being delayed from proper and timely treatment.

Then, starting in the year 2015, Stanford professor and physician-scientist John Ioannidis expressed his concern on the absence of any peer-reviewed research from Theranos published in any medical research literature. Scientists and journalists also soon began to doubt Theranos’s claims surrounding its tests. Along with the increasing questions, some former Theranos employees spoke out about their experiences working for Theranos and exposed how the company faked its testing results by using the traditional blood testing machines of other companies instead of its own machines due to the inaccuracy of Theranos’s own technology. With the help of the former employees’ confessions, in October 2015, journalist John Carreyrou reported in The Wall Street Journal about how Theranos faked its testing results and falsely advertised its technology, drawing more public attention and investigations on the fraud in Theranos.

All the lies Theranos has told have brought consequences. After having a hard time finding buyers, Theranos finally announced its plan to cease operation in September 2018. According to CNN, Elizabeth Holmes, as the founder and former CEO of Theranos, has been charged with “nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud” on trial, facing a maximum sentence of 20 years per count in prison. As of January 3rd, Jury finds Elizabeth Holmes guilty on four of eleven charges of fraud. Holmes’ sentence is expected to be determined at a hearing this week on the three hung charges.

Hi, my name is Yili Bai. I am a senior at SSFS, and it is my third year as a staff writer in Wildezine. I love writing things to record my thoughts and...