British vs. American Humor

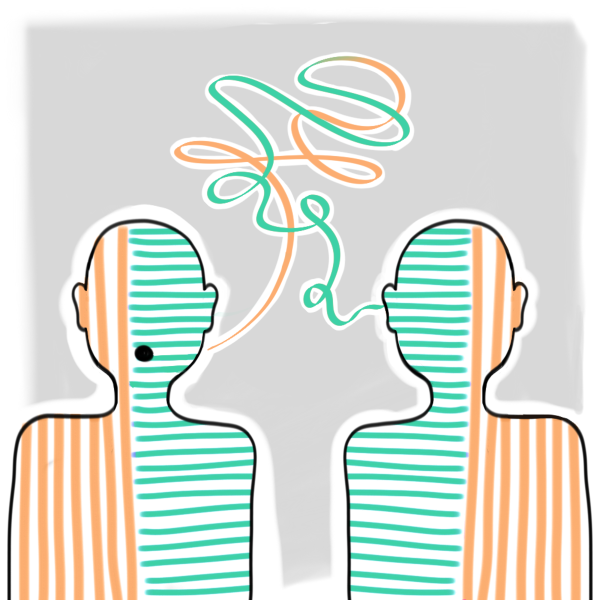

Have you ever laughed hysterically at a meme or joke and subsequently shown it to your friends, only to receive a blank, bewildered stare? Though the moment is awkward, it is often inevitable in a world where every sense of humor is unique. According to the Benign Violation Theory, formulated by Peter Mcgraw, a marketing professor at the University of Colorado who runs the Humor Research Lab, “humor only occurs when something seems wrong, unsettling or threatening (i.e., a violation), but simultaneously seems okay, acceptable, or safe (i.e., benign).” If this statement rings true, then what really differs from person to person is what we find wrong and acceptable and what we find wrong and unacceptable. Within cultures and countries such as England and America, these norms vary.

England has a deep-rooted class system, which is often satirized and mocked in its humor. In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a movie created by the British comedy troupe Monty Python, there’s a scene where King Arthur asks two peasants about who resides in the castle above them. When King Arthur states that he is king of the Britons, the peasants question his authority, saying they didn’t realize they had a king and that they are an “autonomous collective.” The peasants’ disregard for authority and declaration of their own complex system of government shows the wit and self-awareness that define British humor.

British people also tend to tease each other mercilessly and “use sarcasm as both a shield and a weapon” according to a Time magazine interview with British comedian Ricky Gervais. This nonstop “play fighting” is usually a sign of affection among friends, but can be off-putting for Americans and is “sometimes perceived as nasty if the recipients aren’t used to it,” says Gervais. This constant taunting appears in British television shows such as The Office (U.K.), where the boss David Brent is as oblivious and idiotic as Michael Scott in The Office (U.S.) but tends to ridicule his employees more intentionally and directly.

These distinctions in British humor stem from a more cynical population than America; among Americans, there is a common belief that hard work and dedication are rewarded with financial stability and happiness. Just look at popular films like Annie and Rocky. Though their tone, plot, and audience deviate significantly, they share a common story arch of rags to riches or underdog to champion. And Americans eat it up. This belief that good people receive good fortune is not prevalent in the U.K, and although many countries have endured more hardship than England, the pessimism that seeps into a population in trying times seems to have a permanent home in the British. They expect the worst in order to avoid being disillusioned by life, and it is strongly reflected in their distinct sense of humor.

On the other hand, Americans are optimistic, and their humor is overt and exaggerated. They don’t value subtlety and wit to the same degree as Brits; being big, bold, and charismatic are more esteemed than cracking clever jokes. Will Ferrell’s silly, exaggerated impressions are a prime example of this distinct American humor. In movies such as Elf, Talladega Nights and Ron Burgundy, he relies on slapstick and absurdity, turning his characters into caricatures. They’re funny because of how oblivious they are to their own idiocy, and their disconnect between how they perceive themselves and how they are actually perceived adds to the hilarity.

In essence, American humor and British humor reflect their respective cultures. In America, that culture is rooted in optimism and going big or going home. In England, it is rooted in pessimism and unflinching wit.

Hi, my name is Rebecca Megginson. I'm a sophomore at Sandy Spring Friends School who enjoys writing about politics, pop culture, and SSFS life. I joined...